"Echolalia Review" Behind the Scenes: “Decolonizing a stray”

Adele Nwankwo causes an internet fiasco

Source: Bhambra, Gurminder K., Delia Gebrial and Kerem Nisancioglu (eds.). Decolonising the University. Pluto Press. Kindle Edition, p. 2.

“Decolonising” involves a multitude of definitions, interpretations, aims and strategies. To broadly situate its political and methodological coordinates, “decolonising” has two key referents. First, it is a way of thinking about the world which takes colonialism, empire and racism as its empirical and discursive objects of study; it re-situates these phenomena as key shaping forces of the contemporary world, in a context where their role has been systematically effaced from view. Second, it purports to offer alternative ways of thinking about the world and alternative forms of political praxis.

In honour of my ongoing feud with Bitchin’ Kitsch editor Chris Talbot-Heindl (they said so many mean things about me on X! And blocked me! Nooo! How will I ever recover?), I figured I’d kick off my “Behind the Scenes” series, where I delve into the inspiration and mechanics behind each of my published “hoax” poems from Echolalia Review, by taking a look at “Decolonizing a stray.”

It’s no secret that decolonization, a substrate of post-colonialism, is a hot topic in the publishing world. Hop on Goodreads or a commensurate aggregate site, punch in “decolonization lit,” and you’ll be met with quite literally thousands of books on the topic—sometimes, from presses dedicated entirely to it. The poetry end of things is no different. In fact, in addition to full poetry collections (e.g. How to Be a Good Savage and Other Poems [Mikeas Sánchez, Milkweed Editions], Cut to Fortress [Tawahum Bige, Nightwood Editions]), there are whole magazines, such as Decolonial Passage, dedicated to post-colonialism and decolonization, and many others, such as Overland out of Australia, that publish extensively in that category.

Now, I’m not here to say that poets can’t write about decolonization. As I relate in the afterword of Echolalia Review, I think all manner of subject matter is welcome in poetry, so long as it’s addressed purposefully and not in excess. More to the point, it would be cruel to deprive people of the capacity to write about a life- and society-changing topic like this. (Mind you, some pretend to have connections to these topics—and I’ve met some of these “famous” poets in person before—but I’ll save my discussion of that issue for a later date.) But when you reach a point of saturation with any topic or form, it becomes predictable. Worse still, the effect of the writing and its function weaken with each addition.

Years ago, when I first started buying poetry magazines, I happened up the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of the oh-so-ironically named Poetry Is Dead (the mag died later that year). I recall reading it during an English lecture I was supposed to be paying attention to on feminist undertones in some 19th-century novel when I flipped to page 52 of the issue to find Leslie Joy Ahenda’s “How to Decolonize.” (The publisher for the collection she wrote around this time, Moon Jelly House, like Poetry Is Dead, went defunct soon after—as the vast majority of out-of-touch poetry presses and mags do.) In it, Ahenda encourages us to “stop wiping [our] shoes at the door”; to “go back to Africa” when people mean-spiritedly tell us to; to “learn to cook ugali”; to “embrace the word ‘savage’”; to “throw off all the fucking rules they said were so important”; to etc., etc. The piece reads like an instruction manual, with a couple nice turns of phrase thrown in here and there. It’s not an incompetent poem by any means, but even back then, I couldn’t help but wonder how much of this was performative. (Had she, for example, taken her own advice and ripped the front door off her own house and turned it into a coconut-adorned dining table? Surely she still had a front door to her what I pictured was a rented apartment or dorm room.) For whatever reason, though, that poem stuck with me.

Imagine my surprise, then, when weeks later I bought the July/August 2019 issue of the famed Poetry and, in doing so, subjected myself to much the same content as Ahenda’s, a “Global Anglophone Indian Poems” special edition. Here was an issue teeming with content with post-colonial leanings—some of it featuring expert-level treatment, and some of it coming across as pandering and lazy. For instance, a fantastic poem from this set—though, it isn’t very post-colonial in nature—is Mani Rao’s “My Old Woman.” Its engaging fragmentation and hypnotic melancholy make for a brilliant read all the way through. Then, on the flipside, you have 30% or so of the poets in this issue committing the unforgivable sin (in my eyes, anyway) of referencing within their poems the fact that they’re poets writing poetry. (I’ll have another article about this trend soon as well. Poets, please stop telling us you’re poets. For fuck’s sake.) One of the worst poems in this issue by a longshot is Jennifer Robertson’s “We Grew Up in Places That Are Gone.” It’s so short that I can quote the whole thing for you here:

We Grew Up in Places That Are Gone

(Jennifer Robinson)

Why do we look

for sutures and siblings

in all the wrong places,

when Google gives us

22,950,000,000 results

for the word home?

(Poetry, July/August 2019)

Mercifully, this isn’t spiteful post-colonial lit (we’ll get to that—my fake “Baba” poem is a better parody of that particular brand); it’s more like an optimistic take on our current world. But it’s also just vaguely moronic. It’s very nearly on the same tier as Instagram poetry (we’ll also get to that in a follow-up post), with its pseudo-philosophizing and fifth-grade reading level. Like something out of Nayyirah Waheed’s salt. (independently published in 2014), which is demonstrably awful but adored by the usual suspects (https://krui.fm/2016/08/03/decolonize-your-mind-2/). To complement Robinson’s creation, we might as well draw a line-art doodle of a world with Google Maps pins all over it while we’re at it. One of the corollaries of my reading this was discerning that, if you were writing on the subject of post-colonialism, you could write amateurish shit and still get published.

So, I continued my cruise through the literary journals that year and have been on it—sometimes, to my utter dismay—since. And all the while, I’ve encountered poem after poem in the vein of those previously mentioned. (I’ve left out myriad ones from amateur poets, because those would be low-hanging fruit.) I thought things might improve with time—that poets would reflect on the positive changes that have taken place in today’s society and adjust their work according. Instead, it would appear that—at least from what I’ve seen, which is certainly not all that the poetry world has to offer—the resentment underlying so much of post-colonial literature is still around. If anything, it’s intensified in the same way that the longer internet discussions go, the more caustic they become. The group polarization effect is rampant and all-encompassing, and that’s precisely why it feels like nothing in this literary genre has changed, save for its intensity and rate of proliferation, over the years.

But if we were to carefully look for recent changes in the genre beyond its intensity and ubiquity, we might examine the subtopics and approaches these decolonists take in their poems. Originally, it was enough to discuss broader ideas of decolonizing an entire culture, decolonizing an individual person, decolonizing a language. (An aside: Oh, how these poets absolutely loathe writing in English, like Zehra Naqvi communicates in her “Layla Writes a Letter to Majnu in English” (Contemporary Verse 2, Fall 2021). I understand that many unfortunate situations have resulted in groups of people being forced into English monolingualism, and that they may have had their original tongues taken from them—that is, undoubtedly, a tragedy on scale that defies my best efforts of comprehension—but some of these decolonist poets are bi- or multi-lingual, and they could just as well write in other languages, too, instead of declaring that English “will not do.” Naqvi’s speaker “doesn’t know how to love [Majnu]” in English. The language “tastes like metal, bleached, rust.” Why bother, if you’re able to write in another language—as the poet appears to—or are able to learn one and are willing, to put to paper in English how much you dislike English? [Again, if the situation is one of a forced language acquisition, this gripe of mine doesn’t apply.] This speaks to the petty resentment that drives most readers away from contemporary poetry.)

In the present day, however, while these three approaches remain perennially appealing to editors and publishers, poets have moved on to projecting their decolonial inclinations onto physical objects and specific concepts. You can decolonize addiction. You can decolonize assault. You can decolonize pens and pencils. You can decolonize, in a meta way, poetry journals themselves, down to the printing process and distribution. If it exists, it can be decolonized, as the motto would go. The more I stumbled upon poems of this nature, the more I began to wonder where the line would be drawn on what could and couldn’t be decolonized. I remembered back to the Grievance Studies Affair, and the ridiculous content James Lindsay and co. had managed to get published with the purpose of exposing academia for its ludicrousness, and I came up with the idea to run my own similar experiment.

At first, I was going to go with something outright bizarre, such as Japanese gacha games, or something practical, like vending machines, or something overtly farcical, like toilet paper, but I settled on a cat. 1) Because I had a cat at the time whom I loved and who’d had his name changed from Chimaux (shelter name) to something else; and 2) Cats have major ties to historical cultures and world cultures—particularly, those of the Middle East and, loosely by extension, the Nation of Islam movement. I thought all the way back to that first piece I’d seen from Ahenda, its didactic tone and structure, and set out to create my own decolonial poem. After maybe ten minutes and some light editing, I arrived at this:

Decolonizing a stray

(Adele Nwankwo)

Kitty cat. Darling. Explore your new home. Take great, unfettered strides. Get “uppity”—I won’t stop you. No more donated food. No more scratchy cotton blankets to catch broken rest on. You’ve been emancipated. It only cost $49. (You came with a free tote bag and treats—for the easing process.) Still wearing your tag? It claims you as French—Chimaux. You don’t look French. Never trust a slave name. Your gloss-black fur is earth-drawn onyx or gunmetal to them. They write superstitions about you. Broken mirror/steps-under-a-ladder-type shit. What’s seven years of bad luck in your language? Can’t say? Did you have yours stolen, too? Your meows are sibilant and curled, as if formed at the front of the mouth. They instead want to emerge from the diaphragm, collect forgotten phonemes on the way out. Reclaim your syllables, friend. How about a new name? One with an X in it, or an emoji. Self-determination is just that: a linguistic unyoking. Let’s try. Blink if you hear one you like. That one? Good choice. Right, the food. I’ll spare you the IAMS unseasoned chicken pellets. Tonight, Meowkum X, you eat beef suya and lentils with me. Tonight, we feast as the free.

If you read that and thought to yourself “Wow, that’s terrible,” you’re right. It’s the very definition of pandering. I won’t explain all of the tiny jokes contained therein, ’cause that’d ruin the fun of it, but one that stands out is the “Meowkum X” one. You might read it as the speaker assigning their psychological foibles and their cultural struggles to their newly adopted cat. The speaker is, consequently, decolonizing a street cat that has no idea about any of this. It’s probably just fucking hungry and tired of sleeping in a cage, as any animal would be.

On its own, this makes the poem weird, but it doesn’t make it terribly absurd or fraudulent. What does, conversely, is the speaker’s choice of food. As I’ve noted in the “Publication Notes” component of my book, beef suya is a meat dish that calls for garlic and onion powder. Sometimes, whole onion chunks. Anyone who’s ever owned a cat knows not to feed either of these things to a feline, because even tiny doses will cause severe gastrointestinal distress. ⅛ of a teaspoon of garlic powder can kill a cat. So, the speaker in question is, in effect, more focused on ascribing their beliefs onto the cat than they are with caring for it properly.

This was a subtly shitty poem compared to my more outlandish ones elsewhere in Echolalia Review, and I didn’t expect editors to call me out on the “beef suya” deal, unless they actually understood African cuisine and cat care, but the point with this one, to return to my previous comments about post-colonial literature, was to prove, as a part of the broader “Ern Malley” portion of my literary experiment/hoax, that even the most mind-numbing, generic, and blandly resentful decolonization poems could get published if presented the right way.

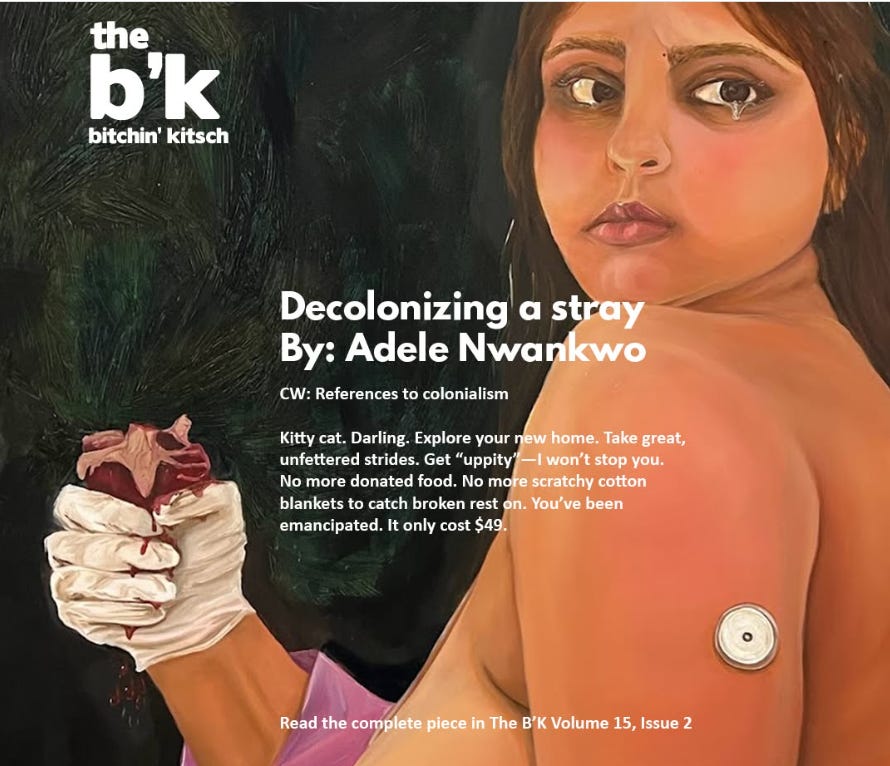

I sent this to three publications under my Adele Nwankwo pseudonym (Nigerian diaspora healthcare worker newbie poet), but my very best friend, Chris of The Bitchin’ Kitsch, picked it up so quickly that the other mags I sent it to didn’t have a chance to consider it. In this sense, it was accepted on my first attempt. Chris offered to pay me a $10 honorarium because I was BIPOC (normally, no payment was offered if you were a non-minority). It appeared in Volume 15, Issue 2 of The Bitchin’ Kitsch in the spring of 2024:

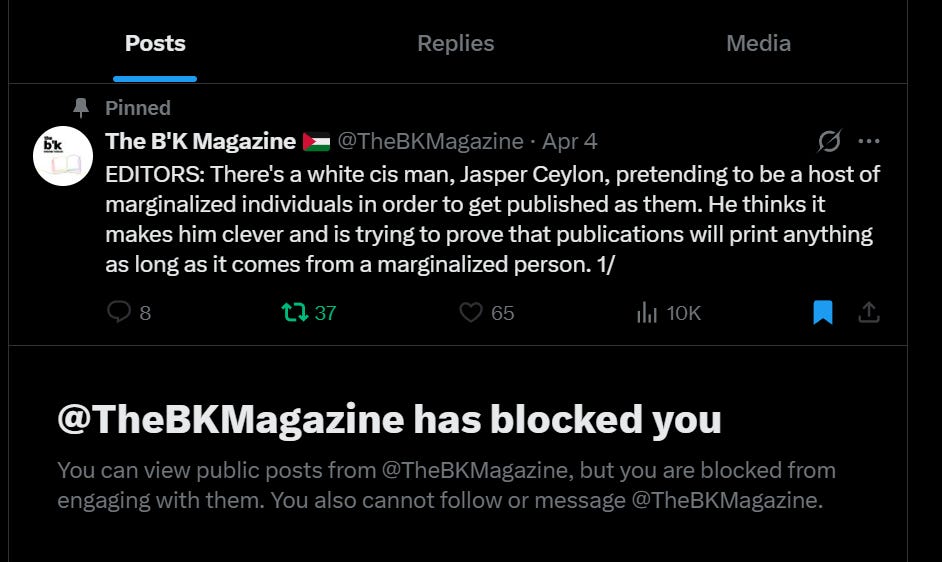

Predictably, once the news finally broke of my deceit, Chris didn’t love hearing that they got punked. And, admittedly, I’ve had a lot of fun watching the related meltdowns on X. Chris has spammed this everywhere, even posting my response email to the one they sent me demanding their $10 honorarium back. (It can’t be sent back—it’s already been donated to charity, just like the proceeds from all the other poems in Echo.) Chris has called me a great number of names, I’m sure, which, hilariously enough, resulted in one of the meltdown posts getting flagged for hate speech, which Chris themselves indirectly accused me of inciting:

For now, I remain the subject of The B’K’s pinned tweet, and other editors from Roi Fainéant and Literary Hub have chimed in to denounce me.

It seems, too, that this has caused some strife within the editorial community. Half of the editors affected wish to use their “whisper network” to notify each other of the dreaded “Adele/B. H./Jasper/etc.” beast without announcing it to the public and giving me attention. These editors have been silently taking down the other Adele content out there. The other half want to confront this issue head-on and publicly. (Editor friends on the inside have confirmed this for me as well.) I can’t estimate the number of emails that have been sent back and forth between these editors and otherwise, but it would appear, for now, many. (Whisper networks are a cowardly construction meant to insulate editors against criticism or backlash. It’s not in the least surprising they’d use one here.)

Controversy aside, my/Adele’s “Decolonizing a stray” poem was meant to take the post-colonial lit crew on and facilitate discussion about where to go from here. Post-colonial literature has an obvious and necessary place in contemporary literature, yet it’s growing stale and lifeless. We’ve heard the greatest hits already. How are we to tell the difference between Tanima’s (she uses a mononym) “Decolonization Ghazal with a Smartphone in my Hand” (Only Poems) and any of the other thousand Gaza Strip-focused decolonization poems out there right now? (I’d wager if we did a live count of how many are being written right this very second, it’d come in around 200.) The problem isn’t the subject matter, per se—it’s the volume, the cheapness, the predictability. If you wanna write a collection of decolonization poems about Fijian culture, go right ahead. But if you write a mawkish poem about decolonizing a mouldy cassava from your backyard, people like me are going to take you to task over it.

Poetry editors love to espouse the sage advice that in an era with so much content, we should all strive to write poetry that offers something new, something unseen (I’m paraphrasing here), but they aren’t good at following their own advice. What I’ve tried to prove with “Decolonizing a stray” (and my “Baba” poem), is that editors and poets have strayed from this maxim and have oversaturated a worthwhile literary genre. If post-colonial literature and decolonial poems are to be taken seriously going forward (again, not my personal cup of nilgiri tea, but lots of people out there enjoy them), the poetry world is going to have to acknowledge the unfortunate truth this part of my literary experiment has revealed. This crisis could be addressed in several ways, including lowering acceptance rates, combining journals, prizing ingenuity, among other things. But the poetry apparatus first has to acknowledge where it’s gone wrong. And as my dear, dear friend Chris has shown, that’s likely not going to happen any time soon. (lol.)

For more of these ridiculous poems and additional content, check out my Echolalia Review: An Anti-Poetry Collection with Pere Ube Press: https://www.amazon.com/Echolalia-Review-Anti-Poetry-Jasper-Ceylon/dp/1738633926/

(For cheap digital copies or review copies, contact me directly @ jasperceylon@protonmail.com.)

And subscribe for more content like this/follow me on X: [at] jceylon2. I’ll be going through the big poems of the collection over the next few months and connecting them to the various ailments in the contemporary poetry and literary worlds. And I’ll be throwing in some fun articles here and there on similar topics, too, including the Pen Name Revolution.

Until next time,

Jasper Ceylon

Satire inside satire inside satire!

Fascinating.

But one question. The misfed stray poem is actually pretty good at what it actually does, i.e. showing up how humans project onto animals in general and more specifically, a certain (pretentious and/or pandering "decolonising") mindset. The curry in the end is a clear clue to it being a pastiche at the minimum, parody for sure; but it really could also work like a funny dramatic monologue for me. So I might be being super thick here, but why do you say it's "bad"?